Earlier on in reading about shoe styles and shoemaking, I was really impressed with wholecuts, especially seamless wholecuts, and a bunch of other patterns that really simplify designs down to the minimum number of pieces. I suppose I’m like most people, in that I’d never seen many shoes like that, or noticed them if I did. Apart from the really impressive making skill those kinds of simplifications imply, there’s often a really neat, minimalist effect.

On the other hand, more recently, and especially since I’ve started trying to think more systematically about my clicking, I’ve been noticing and appreciating some pattern changes that involve more pieces. I’m starting to see that—as usual—it’s not just fewer-good, more-bad kind of thing. There are potentially some trade-offs.

Red Wing versus Irish Setter

Here’s the classic Red Wing moccasin-toe work boot, model 10877:

There is one, unbroken, thick strap of leather running from the backseam all the way around and the toe and back to the backseam. I’ve seen this referred to in various sources as a “one-piece” or “wrap-around” vamp. When I e-mailed Red Wing, Abby there said they don’t really have a technical term for it.

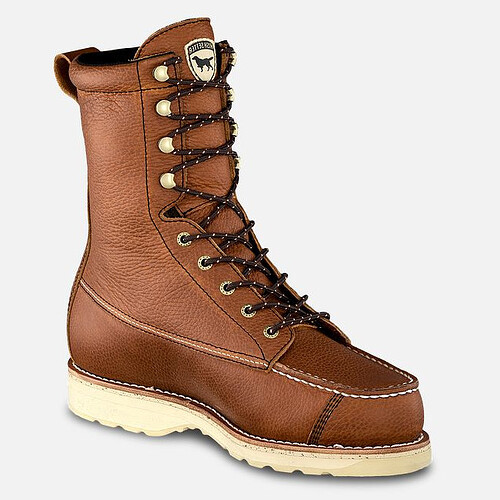

But compare this Wingshooter model, number 896, from Red Wing’s more affordable Irish Setter line:

It’s a very similar design. The vamp still wraps around to the backseam. But the vamp is now three pieces: one at each side and one around the front of the toe.

The continuous look of the Red Wing looks better to my eye. But I can see how the Irish Setter would easier and more efficient to click. I suppose a pattern could also go halfway by making the vamp of two pieces, and stitching together only on the inside or the outside of the foot.

Either way, the quarters on both of these 8" boots remain huge pieces.

Danner Quarters

Speaking of big quarters, I noticed a really interesting pattern detail on some Danner boots.

Here’s their Flashpoint II model, for wildland firefighting:

And here’s their Quarry work boot:

Each quarter here is two pieces, one ending around where the topline of a shoe would be, the other covering the rest of the shaft to the top. That struck me as both leather efficient and potentially better for clicking, compared to the huge one-piece quarters that other Pacific Northwest makers stick to:

One of the trickier clicking problems I’ve run into working on my own boots is that I want the grain or stretch direction of lace-up quarters to resist stretching as the eyelets get pulled tight. DW Frommer’s book on packer boots has a great section on this, where he points out that it’s the exact opposite for pull-ons like cowboy boots, where the strain when donning comes from the wearer pulling up on the pull loops.

Trouble is, as two-dimensional pattern pieces, single-piece lace-up quarters running from the instep across the ankle and up the leg form big bends with angles between 90 and 135 degrees. There isn’t any place on cowhides where the leather is prime and the grain changes direction like that. So the best we can do is compromise. I’ve tried to align the grain perpendicular to the pattern piece, so it’s most resistant to stretch where the instep meets the leg. But that means it’s a little stretchier out by the toe and at the very top. Even just clicking for a small handful of pairs from one hide, I’ve had to compromise further, just given the elbow shape involved.

I’ve seen and heard a few references to Danner being awfully proud of their pickiness on leather and clicking. I imagine splitting big quarters like they do could allow them to better align grain, top and bottom. Of course, I suspect they might be saving some money from efficient clicking like Irish Setter, too.

I’d love to read others’ thoughts.