Galosh Backseams

This seems to have gone pretty well. The steps here were:

- Double check the seam allowance and skive.

- Mark spacing on one side with an overstitch wheel and pierce the holes.

- Lay over the second side and pierce through the holes through the second side.

- Sew face to face.

- Hammer seam open a bit. The biggest progress here actually came from rubbing the side of the hammer face against each lip, rather than banging top-down on the seam.

- With the galosh turned inside-out, I brushed Aquilim 315 water-based contact cement about 5mm before and after the seam and let it go clear, ready to tack. Then I worked the flaps down, cement to cement, with my fingers and a bone folder. This got them most of the way flat.

- Turn the galosh rightside-out again. Turning the seam from convex to concave like this made it easy to flatten the flaps down the rest of the way.

- Mark the stitch lines to the sides of the backseam using an adjustable compass / set of wing dividers—I really like these—running one tine along the backseam. Mark the spacing with an overstitch wheel and pierce the holes, pushing the awl through with one hand between two fingers pressing on the inside of the upper with the other hand. Don’t pierce yourself! Stitch it up.

- Hammer over something curved I used the curved top of a wood chair.

I used 0.020" black braided Maine Thread. I believe the spacing was 8 SPI.

Quarter Seam Stitching

I’d been looking forward to this part. If I get in the right state of mind, I actually enjoy hand saddle stitching plain lines on uppers. But I’m always eager to do the fancier hand stitches.

Aside: I am starting to worry that my nice, wide strips of Cordura eyelet stay backing are going to make ugly creases inboard of the eyelet stay seams.

Materials here were 0.020" braided Maine Thread again. Osborne 517-3 needles, as they recommend.

This was involved, not just because of the fancy stitching, but also just from the challenge of positioning the quarters over the galoshes right. I will probably forget some details, but from memory:

- Bevel the inside edges of the galosh seam allowances. There is going to be a ridge that can be felt, even though the lining will cover the quarter seams. But beveling a bit can’t help. I believe I used a number 2 or 3 Craftool. I like the kit Tandy sells with one handle and a bunch of interchangeable cutters.

- Mark the stitching on the quarters

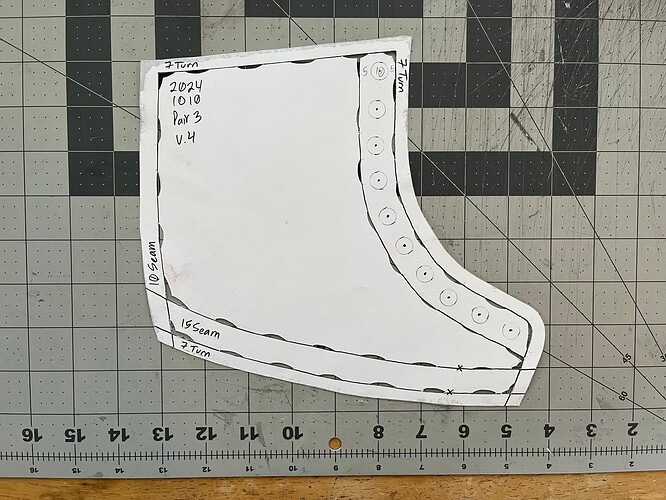

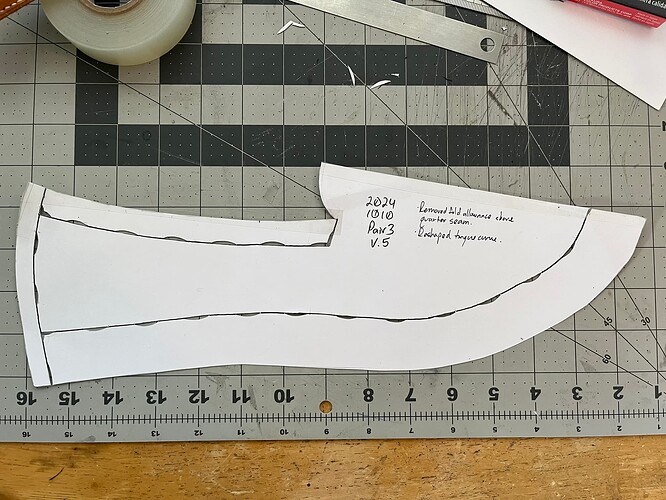

- I gave 7mm turn allowance for the bottoms of the quarters and 15mm seam allowance for quarters and galoshes to overlap. I only ended up using about 5mm of the turn allowance, leaving an extra 2mm. so I had 17mm total to work with.

- I spaced the stitch lines 4, 8, and 12 mm from the edge of the quarter. This was small enough to catch the turned-back edge at the bottom of the quarters and also fit three lines within the original 15mm seam allowance with some margin at the top. I marked these lines with the mini wing dividers again.

- From some studies I did on scrap before this pair, I’d learned that they key to getting a good appearance among the staggered stitch lines, especially around curves, is to mark stitch spacing on one line, then mark the holes for the line next to it freehand, and so on. From a distance, it just likes a cool field of white dashes. Close up, it’s important for the smaller black stitches to line up in staggered rows, like slashes

/ / / / /. If the spacing is off, the eye will see chevrons > > > > instead.

- I marked 10 SPI spacing on the bottom line, nearest the bottom fold of the quarter, with an overstitch wheel. I happened to find an old Osborne No. 10, but 10 SPI is not a common size. 2.5mm point-to-point pricking irons would be nearly identical, though you might have to ignore the direction of slant using a Japanese- or French-style tool. In any case, this is just pricking, not piercing through.

- I marked the prick marks I would actually pierce with a 0.5mm white Sakura Gelly Roll gel pen from the art store. The pattern is Mark - Mark - Skip - Mark - Repeat. This will give alternating stitches of 2.5mm and 5mm in length.

- Copy the white marks to the second and third scratched lines, staggering by one position.

- I pre-pierced the stitching holes over a sheet of cork. As usual with slanted saddle stitch, the slant of the stitches will be the opposite of the slant of the holes.

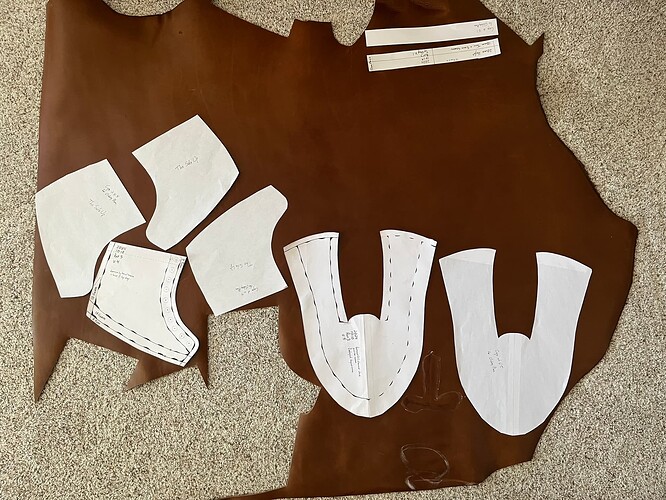

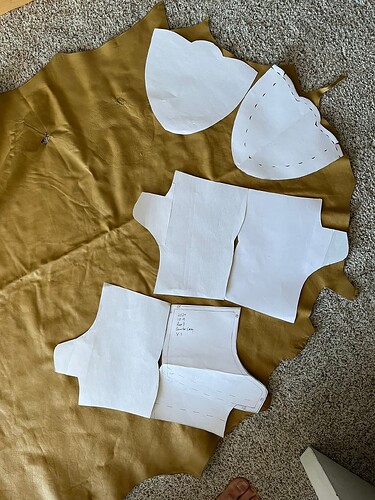

- Mount the quarters.

- I lightly scratched the seam allowance on the outside of the galosh. Mark the seam allowance on the flesh side of the quarters with a pen.

- I brushed Aquilim 315 onto both the galosh and quarters and let tack. This was just to fix for assembly, since the hot stuffed leather here is full of waxes and oils and far from permanently cementable. I could have used double-sided tape or a glue with less wait time instead. And that might have created less residue to deal with later.

- I lay the quarters on, starting from the backseam and working forward. There was a whole awkward dance with feeding the lining pieces and tongues through so everything could come together.

- I basted (or “tacked”) the quarters onto the galoshes through just the second, middle stitch line. I pierced just every third hole through the galoshes and held them together with a running stitch of two-ply hemp thread with beeswax and knotted it at both ends. It help up fine and didn’t ream out the holes too wide for the 0.020" final Maine Thread.

Mistake: Forgot the backstraps would overlap the quarter seams.

I didn’t realize that by backstraps over the quarters would need to overlap the quarter seams for 15mm, and sewed them right to the bottoms earlier on.

I ended up picking the last couple stitches out of the backstraps and starting new threads from underneath. I looped those new threads through some eyelets to keep them still, but they still occasionally dangled around during quarter sewing.

Mistake: Forgot about lining under the tabs

I originally sewed the quarter seams all the way from the backseams to the tabs of the quarters, just sewing the quarters straight to the galoshes. When I then went to filp down the lining attached to the quarters, I realized that they needed to be sewn to the quarters under the tabs if they were going to be held there with anything but ahesive.

So I picked the last few stitches of each of the quarter seam lines, trimmed the quarter linings to fit the tabs, and sewed everything back, including the lining in two out of three of the quarter seam stitch lines. I didn’t sew the lining under the bottom-most seams, because I didn’t want the lining to peek out under the turns at the bottoms of the quarter tabs. Who would ever look under there besides me, I have no clue.

Mistake: Started marking the stitching from the wrong direction

I began marking the stitch pattern back at the backseams, where it would be partially covered by the backstraps. That meant I didn’t get consistency in how the pattern ended up at the tabs, where it will actually be quite visible.

I should have started marking the pattern at the tabs, choosing specifically how I wanted it to end there.

Thoughts on “Freehand” Saddle Stitching

When I did wallets and cases and notebook covers in leather in the past, I nearly always stitched in a pony. That’s not practical for most seams on the uppers I’ve done so far. Most lines curve, and even the “straight” ones like over curved surfaces.

This time, I tried doing a few lines with a couple different styles:

-

“Saddle Style”: The backside is hidden from view at all times. You pierce holes with the awl as you stitch, not in advance. Your non-dominant hand feels for the point of the awl after it comes through, and you use that feeling to find the hole and push the needle through from the backside.

-

“Leathecraft Style”. Pre-pierce all the holes before stitching. Turn the upper back and forth so you can see the hole you’re aiming for each time. Make sure you have good light and wear any glasses you need for your eyesight.

I expected to find the saddle stitch much easier than flipping the upper around, but I had the opposite experience. I can’t tell which lines were stitched which way by appearance, but I was faster and smoother handling just two needles into pre-pierced holes. I think a lot of it had to do with how awkward it could be to handle awl and needle in my right hand. I’m pretty good in a stitching pony, after practice over several years. But the curves involved and lack of anything sturdy to push against with the awl—no big saddle on a tree, no stitching pony holding a small piece immobile—made it awkward.

I also remembered an old trick. You can take neodymium magnets and stick them together through your shirt, creating little magnetic rests where you can park your needles, rather than sticking them in your mouth or letting them dangle:

I actually set mine lower than this, down over my stomach and closer to the work. But it was hard to get a good picture of that.

For anyone with a pony, it’s nice to countersink and epoxy some small magnets into the jaws.